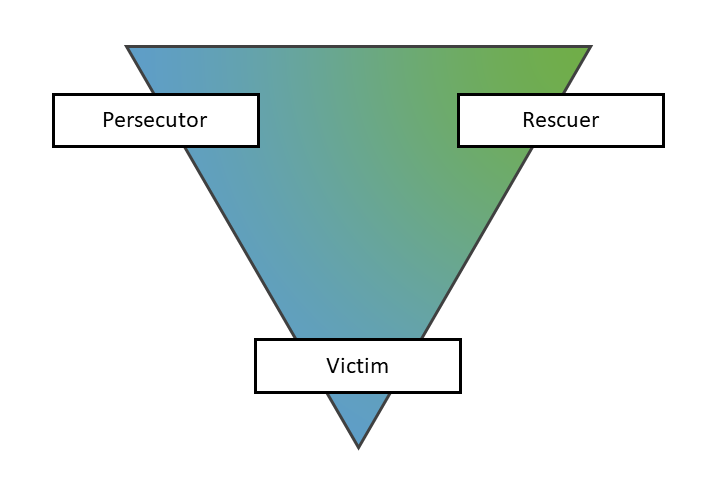

The “drama triangle” is a powerful insight into relationships in social work organisations. It applies as equally to professional peer relationships as it does to relationships with service users. The drama triangle theory comes from the work of Stephen B Karpman and transactional analysis. The risk for practitioners and managers comes from not recognising when we are actually in the “drama triangle”.

Understanding the “drama triangle” helps all of us recognise when we have slipped into unhealthy patterns of management or responses to others. These responses can completely block organisations, teams, and case workers from moving things forward. Understanding it will make you a better senior manager, a better team manager and a better social worker.

So what is the “drama triangle” in social work?

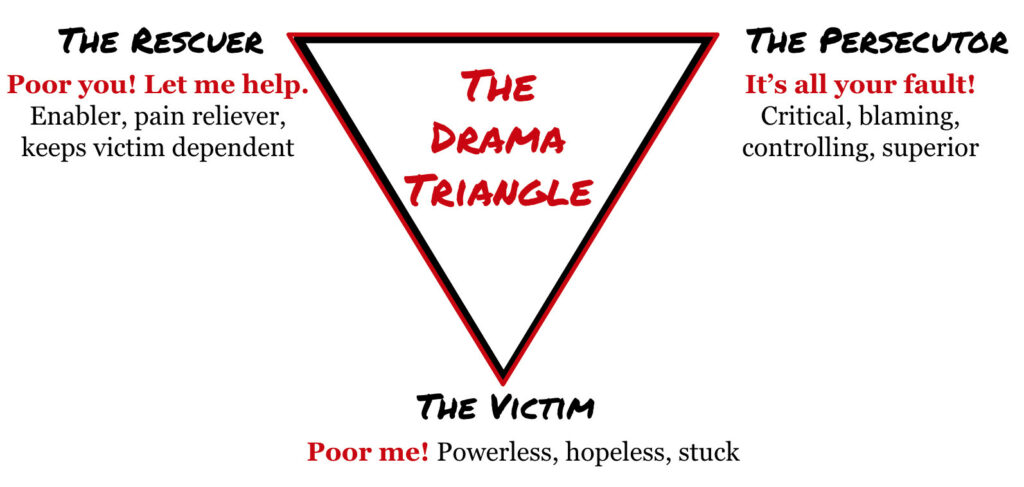

The “drama triangle “is made of three roles – persecutor, victim and rescuer. Each of these roles brings its own rewards and is own cost. Lets look at each one as they might operate in a local authority social work team or service.

Persecutor:

This is the person who is appalled at the failures of the organisation or their direct reports. They might get angry, they might shout, they might express righteous indignation about the quality of social work practice or reports they receive. They will do a lot of finger wagging, insist on compliance, start to micro manage and at times might bully staff.

The rewards from this position are immediate power, control, the gratification of righteous indignation, displacement of responsibility, and a strong sense of moral superiority.

But costs come with this. You become responsible for fixing things. This approach creates a culture of fear in the organisation, and a focus on compliance with no real engagement. It leads to lack of investment and trust in the persecutor, and the organisation. This creates helplessness and victims. It becomes counterproductive in terms of results. For the persecutor, this becomes a very lonely place, ultimately.

Although not limited to this, one will often see this being classically played out in social work after a poor inspection result, or when things go wrong.

Victim:

The victim will always have a narrative about how it is so unfair, so hard, how under valued they are, how they have too much on their case load, how they lack support. Their narrative blames the other, usually managers, or maybe service users. The victim’s narrative doesn’t take responsibility, offer any solutions and is ultimately whiny.

The rewards for this position are that you don’t have to take any actual responsibility for what is going wrong. You get people around you trying to rescue you and you attract a certain amount of sympathy.

The cost however is powerlessness. You feel stuck, it’s pretty miserable to be a victim and people eventually try to avoid you. You are always someone who is done to.

Sometimes social workers genuinely have unfair workloads, but the victim stance doesn’t contribute to solutions.

Rescuer:

The rescuer tries to rescue the victim or the persecutor by jumping in with the offer to solve things. “I’ll do that report”, “leave that with me”, “its okay”, “I’ll hold that case, take that visit”. Then they add another task to their overloaded schedule.

Many of us as managers know this temptation. Rather than having the challenging conversation that needs to be had to get the person to do the work properly, they find it easier to just take it over. Or to pacify a persecutor they will offer to resolve the problem, which may not be entirely in their gift.

The rewards from this are to feel in control, to feel needed, to feel superior as the only person who can fix this.

The costs though are high, because rescuers take on other peoples’ work and they quickly become overwhelmed. They become martyrs. Ultimately this role facilitates the persecutor and victim dysfunctions in the team or organisation without addressing any of the core issues.

Service Users:

We all easily recognise these roles in relationships with service users. How many of us know some workers or managers or external agencies at some point who have behaved as persecutors towards certain families.

Probably everyone know families who behave as perpetual victims. Who blame everyone, the school, the police, especially the social worker for their woes. Who don’t seek solutions, but will frequently find a reason to complain, or displace responsibility elsewhere.

We will also recognise the social work rescuer who focuses on the housing issue when the real issue is parenting. Or the rescuer who jumps in with solutions and advice, is always available, no matter what time of day or night and who creates dependency. Or the worker who over identifies with a family.

Solutions:

The antidote to the drama triangle is the use of coaching responses – according to Michael Bungay Stanier in his book “The Coaching Habit”.

To help escape the rescuer and victim role Michael Bungay Stanier proposes a shift in approach. He recommends taking a more coaching approach to work problems. As a leader he sees his role as not being there to give “the answer”, but to facilitate others to find the answers. He believes that you knowing the answer is a safety net to help people find the answers. This is applicable to social workers with service users, managers in supervision and quality assurance work.

To put it briefly he recommends the following:

- Be lazier about solving other people’s problems for them – literally stop jumping in with solutions and answers

- Instead be more curious and ask more questions

- Turn the questions back to the other person to answer e.g. so what do you think the problem is? So what could you could do to help that? So what solutions do you see?

For more on how a coaching approach can help see the follow up article (coming soon).

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.